Plan for research:

- Waves of feminism

- Feminism in todays society

- Gender role constructs

- Mans oppression

- Generation Z

- Gender neutral

Waves of Feminism

Source:

https://www.progressivewomensleadership.com/a-brief-history-the-three-waves-of-feminism/- Waves of feminism

- Feminism in todays society

- Gender role constructs

- Mans oppression

- Generation Z

- Gender neutral

Waves of Feminism

Source:

The first wave (1830’s – early 1900’s): Women’s fight for equal contract and property rights

Often taken for granted, women in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, realised that they must first gain political power (including the right to vote) to bring about change was how to fuel the fire. Their political agenda expanded to issues concerning sexual, reproductive and economic matters. The seed was planted that women have the potential to contribute just as much if not more than men.

The second wave (1960’s-1980’s): Broadening the debate

Coming off the heels of World War II, the second wave of feminism focused on the workplace, sexuality, family and reproductive rights. During a time when the United States was already trying to restructure itself, it was perceived that women had met their equality goals with the exception of the failure of the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment (which has still yet to be passed).

This time is often dismissed as offensive, outdated and obsessed with middle class white women’s problems. Conversely, many women during the second wave were initially part of the Black Civil Rights Movement, Anti Vietnam Movement, Chicano Rights Movement, Asian-American Civil Rights Movement, Gay and Lesbian Movement and many other groups fighting for equality. Many of the women supporters of the aforementioned groups felt their voices were not being heard and felt that in order to gain respect in co-ed organisations they first needed to address gender equality concerns.

Women cared so much about these civil issues that they wanted to strengthen their voices by first fighting for gender equality to ensure they would be heard.

The third wave (1990’s – present): The “micropolitics” of gender equality

Today and unlike the former movements, the term ‘feminist’ is received less critically by the female population due to the varying feminist outlooks. There are the ego-cultural feminists, the radicals, the liberal/reforms, the electoral, academic, ecofeminists… the list goes on. We are still fighting for acceptance and a true understanding of the term ‘feminism,’ it should be noted that we have made tremendous progress since the first wave. It is a term that has been unfairly associated first, with ladies in hoop skirts and ringlet curls, then followed by butch, man-hating women. Due to the range of feminist issues today, it is much harder to put a label on what a feminist looks like.The main issues we face today were prefaced by the work done by the previous waves of women. We are still working to vanquish the disparities in male and female pay and the reproductive rights of women. We are working to end violence against women in our nation as well as others.

Source: http://www.pacificu.edu/about-us/news-events/four-waves-feminism

It is common to speak of three phases of modern feminism; however, there is little consensus as to how to characterize these three waves or what to do with women's movements before the late nineteenth century. Making the landscape even harder to navigate, a new silhouette is emerging on the horizon and taking the shape of a fourth wave of feminism.

Some thinkers have sought to locate the roots of feminism in ancient Greece with Sappho (d. c. 570 BCE), or the medieval world with Hildegard of Bingen (d. 1179) or Christine de Pisan (d. 1434). Certainly Olympes de Gouge (d. 1791), Mary Wollstonecraft (d. 1797) and Jane Austen (d. 1817) are foremothers of the modern women's movement. All of these people advocated for the dignity, intelligence, and basic human potential of the female sex. However, it was not until the late nineteenth century that the efforts for women's equal rights coalesced into a clearly identifiable and self-conscious movement, or rather a series of movements.

The first wave of feminism took place in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, emerging out of an environment of urban industrialism and liberal, socialist politics. The goal of this wave was to open up opportunities for women, with a focus on suffrage. The wave formally began at the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 when three hundred men and women rallied to the cause of equality for women. Elizabeth Cady Stanton (d.1902) drafted the Seneca Falls Declaration outlining the new movement's ideology and political strategies.

In its early stages, feminism was interrelated with the temperance and abolitionist movements and gave voice to now-famous activists like the African-American Sojourner Truth (d. 1883), who demanded: "Ain't I a woman?" Victorian America saw women acting in very "un-ladylike" ways (public speaking, demonstrating, stints in jail), which challenged the "cult of domesticity." Discussions about the vote and women's participation in politics led to an examination of the differences between men and women as they were then viewed. Some claimed that women were morally superior to men, and so their presence in the civic sphere would improve public behavior and the political process.

The second wave began in the 1960s and continued into the 90s. This wave unfolded in the context of the anti-war and civil rights movements and the growing self-consciousness of a variety of minority groups around the world. The New Left was on the rise, and the voice of the second wave was increasingly radical. In this phase, sexuality and reproductive rights were dominant issues, and much of the movement's energy was focused on passing the Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution guaranteeing social equality regardless of sex.

This phase began with protests against the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City in 1968 and 1969. Feminists parodied what they held to be a degrading "cattle parade" that reduced women to objects of beauty dominated by a patriarchy that sought to keep them in the home or in dull, low-paying jobs. The radical New York group called the Redstockings staged a counter pageant in which they crowned a sheep as Miss America and threw "oppressive" feminine artifacts such as bras, girdles, high-heels, makeup and false eyelashes into the trashcan.

Because the second wave of feminism found voice amid so many other social movements, it was easily marginalized and viewed as less pressing than, for example, Black Power or efforts to end the war in Vietnam. Feminists reacted by forming women-only organizations (such as NOW) and "consciousness raising" groups. In publications like "The BITCH Manifesto" and "Sisterhood is Powerful," feminists advocated for their place in the sun. The second wave was increasingly theoretical, based on a fusion of neo-Marxism and psycho-analytical theory, and began to associate the subjugation of women with broader critiques of patriarchy, capitalism, normative heterosexuality, and the woman's role as wife and mother. Sex and gender were differentiated—the former being biological, and the later a social construct that varies culture-to-culture and over time.

Whereas the first wave of feminism was generally propelled by middle class, Western, cisgender, white women, the second phase drew in women of color and developing nations, seeking sisterhood and solidarity, claiming "Women's struggle is class struggle." Feminists spoke of women as a social class and coined phrases such as "the personal is political" and "identity politics" in an effort to demonstrate that race, class, and gender oppression are all related. They initiated a concentrated effort to rid society top-to-bottom of sexism, from children's cartoons to the highest levels of government.

One of the strains of this complex and diverse "wave" was the development of women-only spaces and the notion that women working together create a special dynamic that is not possible in mixed-groups, which would ultimately work for the betterment of the entire planet. Women, due whether to their long "subjugation" or to their biology, were thought by some to be more humane, collaborative, inclusive, peaceful, nurturing, democratic, and holistic in their approach to problem solving than men. The term eco-feminism was coined to capture the sense that because of their biological connection to earth and lunar cycles, women were natural advocates of environmentalism.

The third wave of feminism began in the mid-90's and was informed by post-colonial and post-modern thinking. In this phase many constructs were destabilized, including the notions of "universal womanhood," body, gender, sexuality and heteronormativity. An aspect of third wave feminism that mystified the mothers of the earlier feminist movement was the readoption by young feminists of the very lip-stick, high-heels, and cleavage proudly exposed by low cut necklines that the first two phases of the movement identified with male oppression. Pinkfloor expressed this new position when she said that it's possible to have a push-up bra and a brain at the same time.

The "grrls" of the third wave stepped onto the stage as strong and empowered, eschewing victimization and defining feminine beauty for themselves as subjects, not as objects of a sexist patriarchy. They developed a rhetoric of mimicry, which appropriated derogatory terms like "slut" and "bitch" in order to subvert sexist culture and deprive it of verbal weapons. The web is an important tool of "girlie feminism." E-zines have provided "cybergrrls" and "netgrrls" another kind of women-only space. At the same time — rife with the irony of third-wave feminism because cyberspace is disembodied — it permits all users the opportunity to cross gender boundaries, and so the very notion of gender has been unbalanced in a way that encourages experimentation and creative thought.

This is in keeping with the third wave's celebration of ambiguity and refusal to think in terms of "us-them." Most third-wavers refuse to identify as "feminists" and reject the word that they find limiting and exclusionary. Grrl-feminism tends to be global, multi-cultural, and it shuns simple answers or artificial categories of identity, gender, and sexuality. Its transversal politics means that differences such as those of ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, etc. are celebrated and recognized as dynamic, situational, and provisional. Reality is conceived not so much in terms of fixed structures and power relations, but in terms of performance within contingencies. Third wave feminism breaks boundaries.

The fourth wave of feminism is still a captivating silhouette. A writer for Elle Magazine recently interviewed me about the waves of feminism and asked if the second and third waves may have “failed or dialed down” because the social and economic gains had been mostly sparkle, little substance, and whether at some point women substituted equal rights for career and the atomic self. I replied that the second wave of feminism ought not be characterized as having failed, nor was glitter all that it generated. Quite the contrary; many goals of the second wave were met: more women in positions of leadership in higher education, business and politics; abortion rights; access to the pill that increased women’s control over their bodies; more expression and acceptance of female sexuality; general public awareness of the concept of and need for the “rights of women” (though never fully achieved); a solid academic field in feminism, gender and sexuality studies; greater access to education; organizations and legislation for the protection of battered women; women’s support groups and organizations (like NOW and AAUW); an industry in the publication of books by and about women/feminism; public forums for the discussion of women’s rights; and a societal discourse at the popular level about women’s suppression, efforts for reform, and a critique of patriarchy. So, in a sense, if the second wave seemed to have “dialed down,” the lull was in many ways due more to the success of the movement than to any ineffectiveness. In addition to the sense that many women’s needs had been met, feminism’s perceived silence in the 1990s was a response to the successful backlash campaign by the conservative press and media, especially against the word feminism and its purported association with male-bashing and extremism.

However, the second wave only quieted down in the public forum; it did not disappear but retreated into the academic world where it is alive and well—incubating in the academy. Women’s centers and women’s/gender studies have became a staple of virtually all universities and most colleges in the US and Canada (and in many other nations around the word). Scholarship on women’s studies, feminist studies, masculinity studies, and queer studies is prolific, institutionalized, and thriving in virtually all scholarly fields, including the sciences. Academic majors and minors in women’s, feminist, masculinity and queer studies have produced thousands of students with degrees in the subjects. However, generally those programs have generated theorists rather than activists.

Returning to the question the Elle Magazine columnist asked about the third wave and the success or failure of its goals. It is hard to talk about the aims of the third wave because a characteristic of that wave is the rejection of communal, standardized objectives. The third wave does not acknowledge a collective “movement” and does not define itself as a group with common grievances. Third wave women and men are concerned about equal rights, but tend to think the genders have achieved parity or that society is well on its way to delivering it to them. The third wave pushed back against their “mothers” (with grudging gratitude) the way children push away from their parents in order to achieve much needed independence. This wave supports equal rights, but does not have a term like feminism to articulate that notion. For third wavers, struggles are more individual: “We don’t need feminism anymore.”

But the times are changing, and a fourth wave is in the air. A few months ago, a high school student approached one of the staff of the Center for Gender Equity at Pacific University and revealed in a somewhat confessional tone, “I think I’m a feminist!” It was like she was coming out of the closet. Well, perhaps that is the way to view the fourth wave of feminism.

The aims of the second feminist movement were never cemented to the extent that they could survive the complacency of third wavers. The fourth wave of feminism is emerging because (mostly) young women and men realize that the third wave is either overly optimistic or hampered by blinders. Feminism is now moving from the academy and back into the realm of public discourse. Issues that were central to the earliest phases of the women’s movement are receiving national and international attention by mainstream press and politicians: problems like sexual abuse, rape, violence against women, unequal pay, slut-shaming, the pressure on women to conform to a single and unrealistic body-type and the realization that gains in female representation in politics and business, for example, are very slight. It is no longer considered “extreme,” nor is it considered the purview of rarified intellectuals to talk about societal abuse of women, rape on college campus, Title IX, homo and transphobia, unfair pay and work conditions, and the fact that the US has one of the worst records for legally-mandated parental leave and maternity benefits in the world.

Some people who wish to ride this new fourth wave have trouble with the word “feminism,” not just because of its older connotations of radicalism, but because the word feels like it is underpinned by assumptions of a gender binary and an exclusionary subtext: “for women only.” Many fourth wavers who are completely on-board with the movement’s tenants find the term “feminism” sticking in their craws and worry that it is hard to get their message out with a label that raises hackles for a broader audience. Yet the word is winning the day. The generation now coming of age sees that we face serious problems because of the way society genders and is gendered, and we need a strong “in-your-face” word to combat those problems. Feminism no longer just refers to the struggles of women; it is a clarion call for gender equity.

The emerging fourth wavers are not just reincarnations of their second wave grandmothers; they bring to the discussion important perspectives taught by third wave feminism. They speak in terms of intersectionality whereby women’s suppression can only fully be understood in a context of the marginalization of other groups and genders—feminism is part of a larger consciousness of oppression along with racism, ageism, classism, abelism, and sexual orientation (no “ism” to go with that). Among the third wave’s bequests is the importance of inclusion, an acceptance of the sexualized human body as non-threatening, and the role the internet can play in gender-bending and leveling hierarchies. Part of the reason a fourth wave can emerge is because these millennials’ articulation of themselves as “feminists” is their own: not a hand-me-down from grandma. The beauty of the fourth wave is that there is a place in it for all –together. The academic and theoretical apparatus is extensive and well honed in the academy, ready to support a new broad-based activism in the home, in the workplace, and in the streets.

At this point we are still not sure how feminism will

mutate. Will the fourth wave fully materialize and in

what direction? There have always been many feminisms in the movement, not just one ideology, and there have always been tensions, points and counter-points. The political, social and intellectual feminist movements have always been chaotic, multivalenced, and disconcerting; and let's hope they continue to be so; it's a sign that they are thriving.

Feminist figures

Feminism today

Source: http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/international-women-s-day-2016-we-spoke-to-the-women-who-won-t-be-celebrating-a6917506.html

"I stopped identifying as a feminist a few years ago when I was studying rape and discovered that prominent feminist organisations were misrepresenting rape prosecution statistics for political reasons. The Stern Report on Rape later officially confirmed this and also noted that the practice could stop victims coming forward – in other words, feminism was placing ideology before truth and before people. I found that unconscionable. It is still happening. Rape statistics are constantly being misrepresented to frighten women and make them believe they live in a “rape culture”. In fact, successful rape prosecutions are on a par with other crimes at over 50 per cent. Even attrition rates are commensurable to other crimes and victims should not feel there is little chance of receiving justice if they come forward. Our justice system is not failing victims of rape. Rather feminism is failing us and our justice system. I identify as an egalitarian." - Paula Wright, 45

"I am resolutely, unequivocally not a feminist. Saying that, would I have been waving placards alongside the suffragettes? Hell yes. Am I supportive of women’s rights? Of course. But feminism today has been co-opted by a hyper-offended, self-serving, navel-gazing Twitterati mob who mostly care about furthering their own (actually rather privileged) agenda than the plight of their fellow sisterhood who are, like, genuinely oppressed. You know, women living under Sharia Law or the 80 per cent of North Korean female refugees that have become “commodities for purchase.”

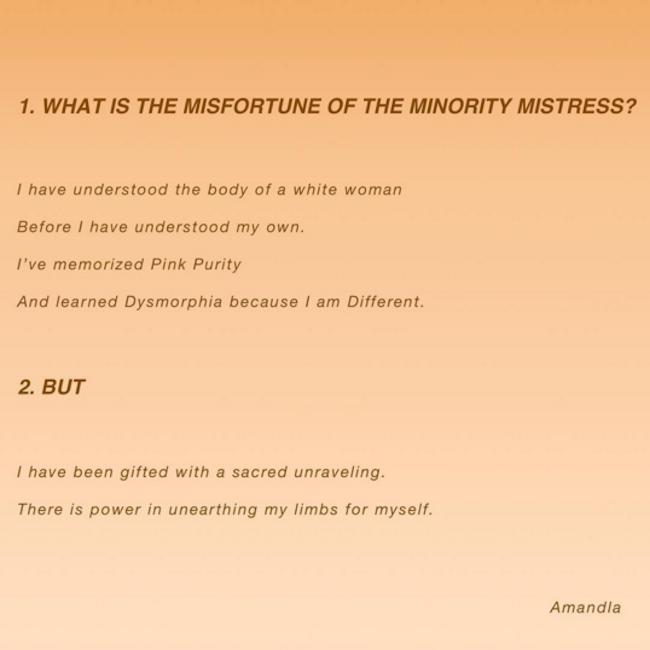

Source: https://i-d.vice.com/en_gb/article/amandla-stenberg-wrote-a-poem-about-race-and-sexuality

Case in point: the International Women’s Day schedule is almost all career-enhancing, work-centric conferences and events for the benefit and advancement of Western women. Suspiciously absent are charitable causes which would really empower oppressed and abused women in the rest of the world that do not have any voice at all." - Ellen Grace Jones, 33.

Vice: https://i-d.vice.com/en_gb/article/amandla-stenberg-wrote-a-poem-about-race-and-sexuality

"Amandla Stenberg wrote a poem about race and sexuality"

Amandla Stenberg is undoubtedly an icon for her generation. Speaking out on a number of important issues, ranging from sexuality to cultural appropriation, the actress has rapidly become a defining voice for young men and women the world over. But that's not to say she's free from struggling to understand her own body in a world that normalises only certain (i.e. white) kinds of beauty. Yesterday, on World Poetry Day, Stenberg shared some poignant words about othered bodies and dysmorphia. "Some thoughts on my consistently shifting relationship w my body/feeling shame for black sexuality," she wrote on Instagram.

Speaking to i-D recently, Stenberg discussed her initial desire to distance herself from the "black component" of her identity. "I straightened my hair and tried to make myself more digestible, but recently I have realised that the black component of my identity is extremely, extremely important. It has completely changed who I am as a human being. I feel like now my identity has gone full circle." We're pleased to see her continue to bring this message of positivity to her army of social followers.

Vice: https://i-d.vice.com/en_gb/article/from-body-loathing-to-slut-shaming-meet-the-17-year-old-whos-simply-had-enough

"from body loathing to slut shaming meet the 17-year-old who’s simply had enough"

Ali Marsh is the 17-year-old student who's been a victim of patriarchal bullshit ever since she first put on a bra. Teased for having breasts, bullied for trying to hide them, and then slut-shamed when she tried to show them off, growing up hasn't always easy for Ali. But after years of intense self-loathing, Ali found feminism and was inspired her to stand up for what she believed in, not take no for an answer, redefine what it means to be a woman, and, ultimately, regain control over her own body.

Through her research she discovered actress, filmmaker, and Free the Nipple founder Lina Esco, who promptly took Ali under her wing. Fresh from staging her very own topless protest - with the newly founded Free the Nipple L.A. - we catch up with the young activist to talk tits, trolls, and why it's so important to free the female nip.

Why is Free the Nipple such an important cause?

It's to get people talking about equality. We have a long way to go, but everyone needs a place to start. I choose to free my nipples to show I am not ashamed. I am proud of who I am, and I truly believe my body is of the same value as the next. Who is to tell us one nipple is legal but another isn't?

What is the story behind Free the Nipple L.A. and what inspired you to found it?

I started leading a group in Los Angeles around six months ago and it took off from there. Growing up is hard enough as it is, but Los Angeles added even more pressure. I couldn't walk down the street without seeing photos of the "ideal woman". In elementary school, I was always in boys clothes, but I developed breasts very early on and it became uncomfortable for me to play sports in a baggy shirt. My mum bought me a sports bra and the first day I wore it I was relentlessly teased. People made fun of me because I had boobs! I started a new middle school a few years later and everyone started to brag about their bras. It was now considered cool to push your boobs up as high as you could and wear the brightest bra possible. I started to wear normal bras and shirts that were a little less baggy. People started calling me a slut. I felt very confused. It was wrong for me to have boobs so I hid them, but then it was wrong to hide them. Finally I started to show them and now that wasn't okay either. I went on a downward spiral of body loathing that often led me to feeling really depressed and alone. I can now say through all that I have become a much more confident and happy person.

Gender Role constructs

http://i-d.vice.com/en_gb/article/could-we-ever-live-in-a-truly-genderless-society?utm_campaign=viceuk&utm_medium=social&utm_source=Facebook

could we ever live in a truly genderless society?

Defining your gender outside of the binary of female or male is something which can often feel rather redundant in mainstream space, for multiple reasons. While so many seek to package us into acceptable female/male categories, our gender identities are constantly tugged and twisted into arbitrary categories designed to make others feel comfortable. When society demands that you, your body, your emotions, your skills, your dress, must fit within a binary, defining as non-binary gender continues to be a tool of community and political empowerment in an otherwise impossibly constrictive gender environment into which we are born.

The gender conversation is something which has been a focus within mainstream media for a while now. Every newspaper and magazine worth reading has been part of the discussion, and it's undeniable that the mainstreaming of discourse surrounding issues such as trans, drag, and gender non-conformity in its many forms has been hugely educational for people who might never normally have come across such discussions. But while the media continues to superficially pick apart normative understandings of gender, why does it feel like attitudes to any form of non-binary gender presentation in public space have not moved forward at all?

Both systemic and personal oppression continues to be a fact of daily life for anyone whose identity questions the socially acceptable gender binary. Much like buying cigarettes or milk, we begin to normalise, and even expect, experiences of abuse linked with our apparently non-binary gender identities. This is unavoidable, it is really quite impossible to move in spaces where being mis-gendered by others isn't on the agenda.

Behind our bedroom doors, or within the four walls of our city's ever dwindling queer spaces, we can find places where one can express, explore, and forget their gender - and these spaces, for the most part, feel safe. But in order to maintain this personal safety within public space one often has to be covert, and offer a much more 'digestible' presentation of our gender non-conforming selves in order to be received by the world.

So while we feel as though we are becoming more accepted online and in the pages of print journalism, everything from aggressive prejudice to subtle mis-gendering remains a constant part of our social landscape, however digestible we may appear to a mainstream audience.

Everyone's binary understanding of the world begins the moment we're born. We are all deprived of the skills — in language, in education, in aesthetics — to comprehend the body, and ultimately the person, outside of a female/male gendered system 'what long, girly eyelashes they have', 'Wow you have muscular arms', 'your voice is so high, like a little girl!', 'Mummy what's wrong with that boy, he's wearing a skirt?'

Our gendered discourse is questioned incredibly infrequently in our developing years. Both home and school often feel like a fight to stay un-bullied; who has time to work on their personal gender definitions when battling through a rather perfunctory, yet voluminous, education and the complex social hierarchy that is school?

So here we have it: we are birthed into, trained with, conditioned by, employed in, legalised via, described using, binary gender categories. Exploring one's own binary non-conformism is continuous throughout life and often has to be a process of self education. As we continue to come up against yet more structures that aim to tether us to the categories of one or the other gender we are constantly remodelling our own gender identities, while our critics remain un-questioning of their binary position. Continued education of those we interact with on a daily a basis is potentially a means toward feeling more accepted, but why does the onus of educating others fall upon those who do not benefit from fitting within the socially advantageous gender binary in the first place?

In our own space, once we have battled with the apparent 'failure to fit into the socially acceptable binary' and have worked hard to create a safe space (perhaps alone, perhaps in a wonderfully supportive group of allies) we can temporarily escape our body longing. It is the outside world's categorisation and gendering of us that results in damaging, belittling and potentially traumatic gendering. And of course we can express our gender, or our rejection of it full stop, in any way we feel in public space, but it is others who will continue to jeopardise our safety for as long as we are seen through their binary gender lens. While the media continue to paw over the same aspects of the gender conversation, it is our language and our categories which everyone should be questioning, in the on-going pursuit of demolishing gender stereotypes.

Man Oppression

Source: http://www.theatlantic.com/sexes/archive/2013/05/when-men-experience-sexism/276355/

As Jennifer Ludden reports, after divorce men can face burdensome alimony payments even in situations where their ex-wives are capable of working and earning a substantial income. Even in cases where temporary alimony makes sense—as when a spouse has quit a job to raise the children—it's hard to understand the need for lifetime alimony payments, given women's current levels of workforce participation. As one alimony-paying ex-husband says, "The theory behind this was fine back in the '50s, when everybody was a housewife and stayed home." But today, it looks like an antiquated perpetuation of retrograde gender roles—a perpetuation which, disproportionately, harms men. Many of these examples—particularly the points about custody inequities and conscription—are popular with men's rights activists. MRAs tend to deploy the arguments as evidence that men are oppressed by women and, especially, by feminists. Yet, what's striking about instances of sexism against men is how often the perpetrators are not women but other men. The gendercides in Serbia and Rwanda were committed against men, not by feminists, but by other men. Prison rape is, again, overwhelmingly committed by men against other men—with (often male) prison officials sitting by and shrugging. Conscription in the U.S. was implemented overwhelmingly by male civilian politicians and military authorities, not by women.

Defining your gender outside of the binary of female or male is something which can often feel rather redundant in mainstream space, for multiple reasons. While so many seek to package us into acceptable female/male categories, our gender identities are constantly tugged and twisted into arbitrary categories designed to make others feel comfortable. When society demands that you, your body, your emotions, your skills, your dress, must fit within a binary, defining as non-binary gender continues to be a tool of community and political empowerment in an otherwise impossibly constrictive gender environment into which we are born.

The gender conversation is something which has been a focus within mainstream media for a while now. Every newspaper and magazine worth reading has been part of the discussion, and it's undeniable that the mainstreaming of discourse surrounding issues such as trans, drag, and gender non-conformity in its many forms has been hugely educational for people who might never normally have come across such discussions. But while the media continues to superficially pick apart normative understandings of gender, why does it feel like attitudes to any form of non-binary gender presentation in public space have not moved forward at all?

Both systemic and personal oppression continues to be a fact of daily life for anyone whose identity questions the socially acceptable gender binary. Much like buying cigarettes or milk, we begin to normalise, and even expect, experiences of abuse linked with our apparently non-binary gender identities. This is unavoidable, it is really quite impossible to move in spaces where being mis-gendered by others isn't on the agenda.

Behind our bedroom doors, or within the four walls of our city's ever dwindling queer spaces, we can find places where one can express, explore, and forget their gender - and these spaces, for the most part, feel safe. But in order to maintain this personal safety within public space one often has to be covert, and offer a much more 'digestible' presentation of our gender non-conforming selves in order to be received by the world.

So while we feel as though we are becoming more accepted online and in the pages of print journalism, everything from aggressive prejudice to subtle mis-gendering remains a constant part of our social landscape, however digestible we may appear to a mainstream audience.

Everyone's binary understanding of the world begins the moment we're born. We are all deprived of the skills — in language, in education, in aesthetics — to comprehend the body, and ultimately the person, outside of a female/male gendered system 'what long, girly eyelashes they have', 'Wow you have muscular arms', 'your voice is so high, like a little girl!', 'Mummy what's wrong with that boy, he's wearing a skirt?'

Our gendered discourse is questioned incredibly infrequently in our developing years. Both home and school often feel like a fight to stay un-bullied; who has time to work on their personal gender definitions when battling through a rather perfunctory, yet voluminous, education and the complex social hierarchy that is school?

So here we have it: we are birthed into, trained with, conditioned by, employed in, legalised via, described using, binary gender categories. Exploring one's own binary non-conformism is continuous throughout life and often has to be a process of self education. As we continue to come up against yet more structures that aim to tether us to the categories of one or the other gender we are constantly remodelling our own gender identities, while our critics remain un-questioning of their binary position. Continued education of those we interact with on a daily a basis is potentially a means toward feeling more accepted, but why does the onus of educating others fall upon those who do not benefit from fitting within the socially advantageous gender binary in the first place?

In our own space, once we have battled with the apparent 'failure to fit into the socially acceptable binary' and have worked hard to create a safe space (perhaps alone, perhaps in a wonderfully supportive group of allies) we can temporarily escape our body longing. It is the outside world's categorisation and gendering of us that results in damaging, belittling and potentially traumatic gendering. And of course we can express our gender, or our rejection of it full stop, in any way we feel in public space, but it is others who will continue to jeopardise our safety for as long as we are seen through their binary gender lens. While the media continue to paw over the same aspects of the gender conversation, it is our language and our categories which everyone should be questioning, in the on-going pursuit of demolishing gender stereotypes.

Man Oppression

Source: http://www.theatlantic.com/sexes/archive/2013/05/when-men-experience-sexism/276355/

As Jennifer Ludden reports, after divorce men can face burdensome alimony payments even in situations where their ex-wives are capable of working and earning a substantial income. Even in cases where temporary alimony makes sense—as when a spouse has quit a job to raise the children—it's hard to understand the need for lifetime alimony payments, given women's current levels of workforce participation. As one alimony-paying ex-husband says, "The theory behind this was fine back in the '50s, when everybody was a housewife and stayed home." But today, it looks like an antiquated perpetuation of retrograde gender roles—a perpetuation which, disproportionately, harms men. Many of these examples—particularly the points about custody inequities and conscription—are popular with men's rights activists. MRAs tend to deploy the arguments as evidence that men are oppressed by women and, especially, by feminists. Yet, what's striking about instances of sexism against men is how often the perpetrators are not women but other men. The gendercides in Serbia and Rwanda were committed against men, not by feminists, but by other men. Prison rape is, again, overwhelmingly committed by men against other men—with (often male) prison officials sitting by and shrugging. Conscription in the U.S. was implemented overwhelmingly by male civilian politicians and military authorities, not by women.